In 1989, when the idea of forging a community online was still niche enough to feel like a radical dream, an essay in the inaugural issue of cyberpunk magazine Mondo2000 already had the audacity to ask: have we missed the revolution? Penned by Lee Felsenstein, the text takes stock of the potential, promised by the advent of the personal computer, for new technologies to contest control and engender greater forms of interpersonal connection. This opportunity, of course, was not a given. “If people can gain control over their own channels, and have the technological means available to do that directly”, he wrote, “then they can control their own communities.” If the revolution in question was not to be missed, then ownership and control over one’s own means of communication were central affordances of any technology that would lend itself to genuine community-building, or what Felsenstein called “convivial” interaction.

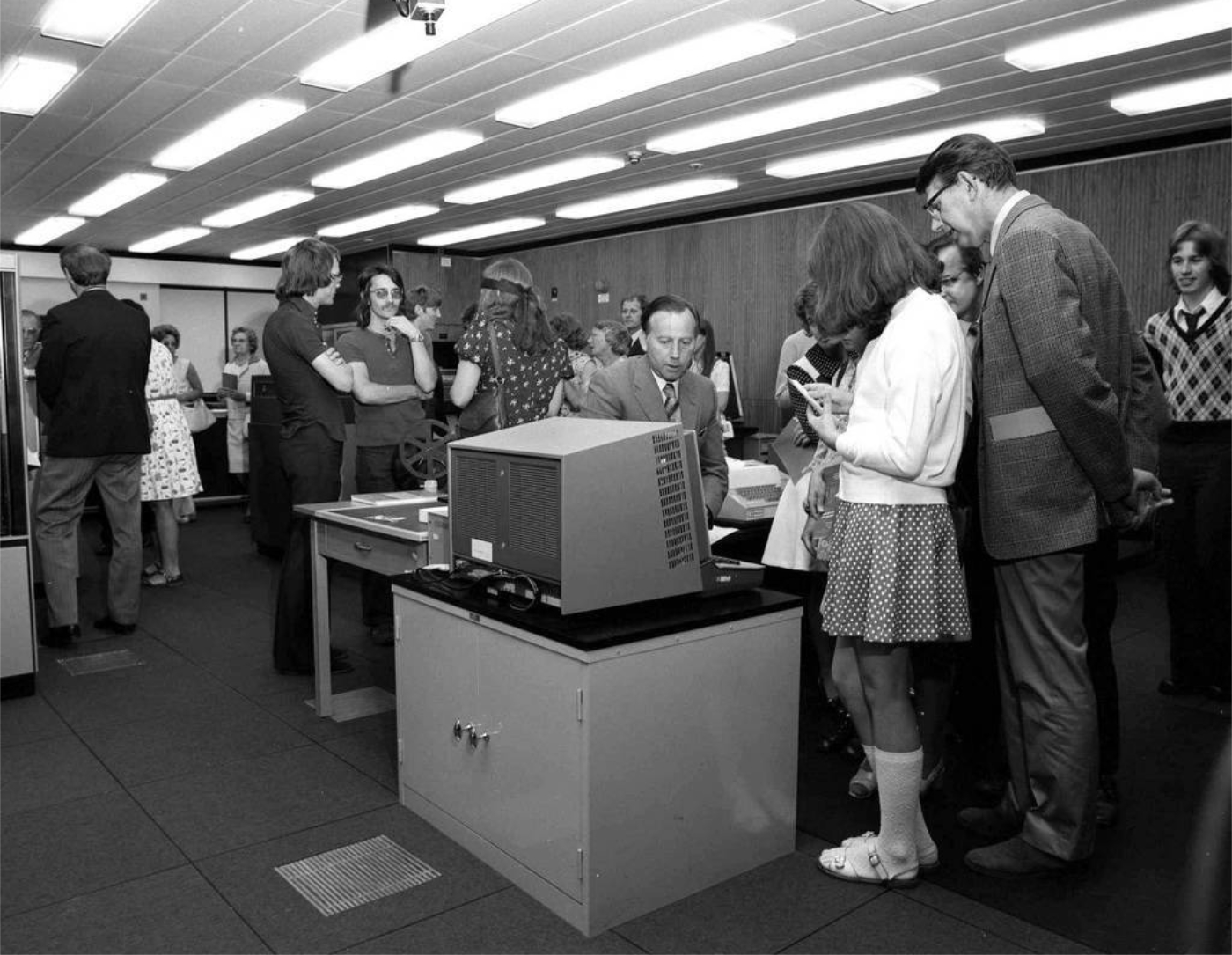

His use of that term brings to mind Ivan Illich, whose “Tools for Conviviality” expressed the need for technology that can be grasped and reconstructed – tools of “high, independent efficiency” that a user could take responsibility for. Convivial tools are the opposite of industrial or institutional; Illich argued for making things usable and re-inserting the personal dimension into their construction. This was 1973, and he was talking about urban planning, but the resonance with Felsenstein’s point doesn’t seem so far a reach. If personal computing was indeed to offer any radical possibility, and especially any claim to agency over the ability to build and be in communities, it ought to be grounded in simple, accessible tools that we ourselves can operate.

From a present standpoint, we could understand both Illich and Felsenstein’s texts as calls for human-scale technology. Simplicity is a central ingredient of this prescription; it’s hard to feel much ownership over something that one can’t use, manipulate, or maintain without deferring to an external expert every time something needs tinkering under the hood. In the decades since these treatises’ publication, personal computing has become totally commonplace, yet, with the elaboration of social networking and Cambrian Explosion of communication tools brought about by Web 2.0, it feels increasingly, and noticeably, less convivial.

Why did this trajectory – and not one of “personal computing leagues” and ad-hoc hacking, of the nature Felsenstein and his Mondo co-conspirators so passionately envisioned – take hold? My hypothesis is that, as Rich Hickey lays out, simplicity actually demands a lot of work. In a culture of convenience, the concerted and enthusiastic effort necessary to achieve real agency over our tools can, paradoxically, come across as prohibitively hard. Yet conflating accessibility with frictionlessness works to our collective detriment. The technologies capable of fostering conviviality ask something of us: engagement, patience, the will to understand. In our offline social lives, these are accepted as necessary labors of love: intimacy without investment is an impossible, irresponsible fantasy. To invoke the oft-quoted Simone Weil, “attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity.”

And as we well know, in the present mediatic environment – tellingly termed the “attention economy” – the dynamics of directing our focus online are deeply broken. Is it any surprise that, on the platforms that have pioneered a business model out of stealing and selling that attention, community and conviviality feel so hard to come by? Effort, labor, and understanding are fundamental to relationships online and off. But the spaces where we’re meant to share these qualities online disingenuously sell us (or, rather, do they buy us?) with promises of ease that amount to empty calories, or worse.

By removing friction from the equation (think: Log In With Facebook), they wall us in and transform our connections, conducted within their borders, into spaces of extraction. The mainstream communications platforms we have access to today are marketized to the hilt. Our interactions and the relational graphs they chart – in short, the tender data of our sociality – is made into fodder for surveillance capitalism. When nothing short of interpersonal intimacy is on the line, we ought to be very concerned with what is being occulted away in the name of convenience.

If we want to create technologies that are conducive to meaningful community, where “engagement” is not just a quantitative metric or empty piece of advertising parlance, then, we need to re-orient our values beyond “ease of use”. Like the relationships that we build within them, our platforms should yield satisfaction precisely because they’re non-trivial; they command effort, which is another way of saying they require engagement with the world. Attention; generosity. In step with these values, I’m inspired to ask: what would a convivial social network look and feel like? Human-scale, peer-to-peer, open-source, and non-extractive are all descriptors that come to mind. You can probably anticipate where I’m going with this: a network with many of these merits exists today, ready to be used, tinkered with, and built on top of, and if you’re reading this, you’re probably familiar with it.

Getting started on Urbit takes some work: investment in address space; effort to acquire a planet; possibly even bearing with some confusion during the booting process if you, like me, are an armchair network theorist who often shies away from the technical. But these costs are up-front, not black-boxed out of sight or hidden in an epic-length user agreement. Once it’s up and running, it even feels, dare I say, easy, though the healthy extension of my comfort zone that getting onto the network entailed – especially when I joined in November, a few months shy of the L2 rollout – sticks in my mind. It reminds me of the dynamics that have strengthened my closest relationships online and off: the ability to navigate challenges together and find a connection strengthened, not diminished, by our shared time spent swimming around in that vulnerable space of learning. By re-materializing a little bit of the friction of computing, not gatekeeping but commanding effortful engagement, Urbit has created a platform that is purpose-built for conviviality.