Alongside the v0.8.0 launch we released the latest version of Landscape – Urbit's prototype user interface. Codenamed “Modulo,” it's our vision of an Urbit UI designed for everyday use. Most importantly, it’s the beginning of an interface that has access to the entire Arvo OS, rather than just one facet. Previous iterations of Landscape solely made use of the Hall messaging protocol.

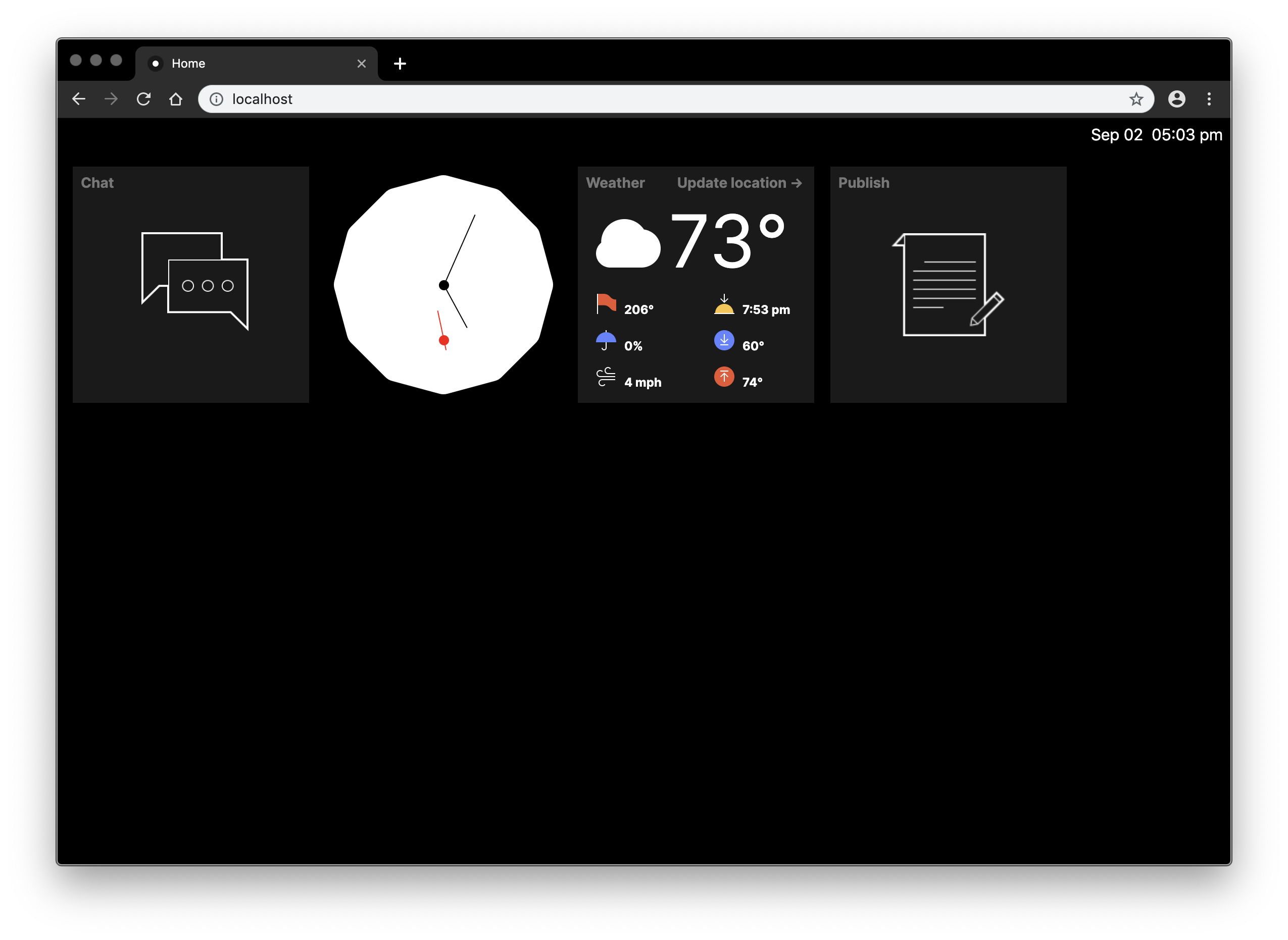

Served after installation on your ship’s HTTPS port, it allows you to interact with Arvo through a web interface built with Indigo, our new UI design language. It has a home screen, which exposes ‘tiles’ for each Landscape application – each able to integrate and customise information from elsewhere in the system and from the broader internet – and connects them to full-screen, graphical applications.

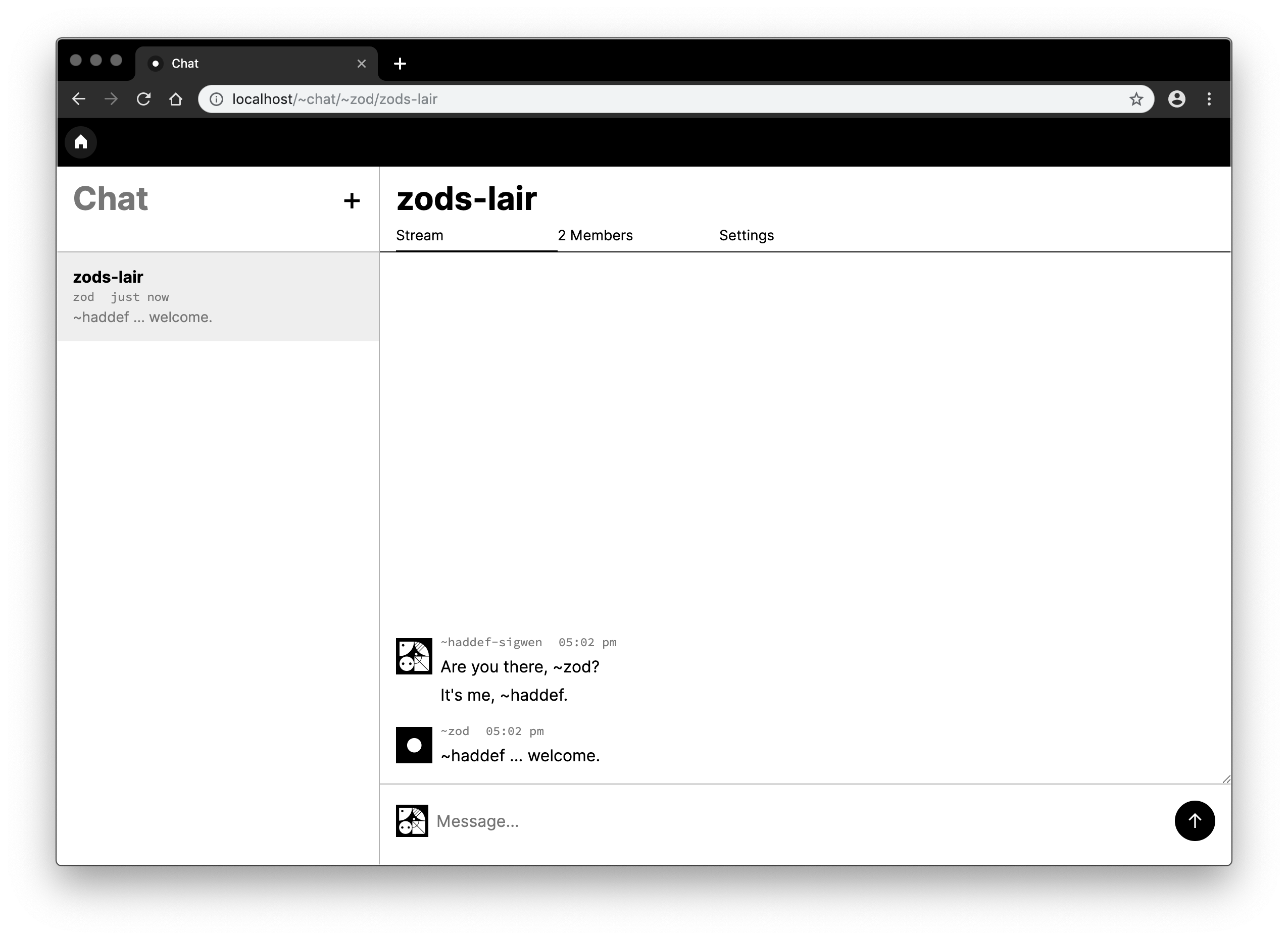

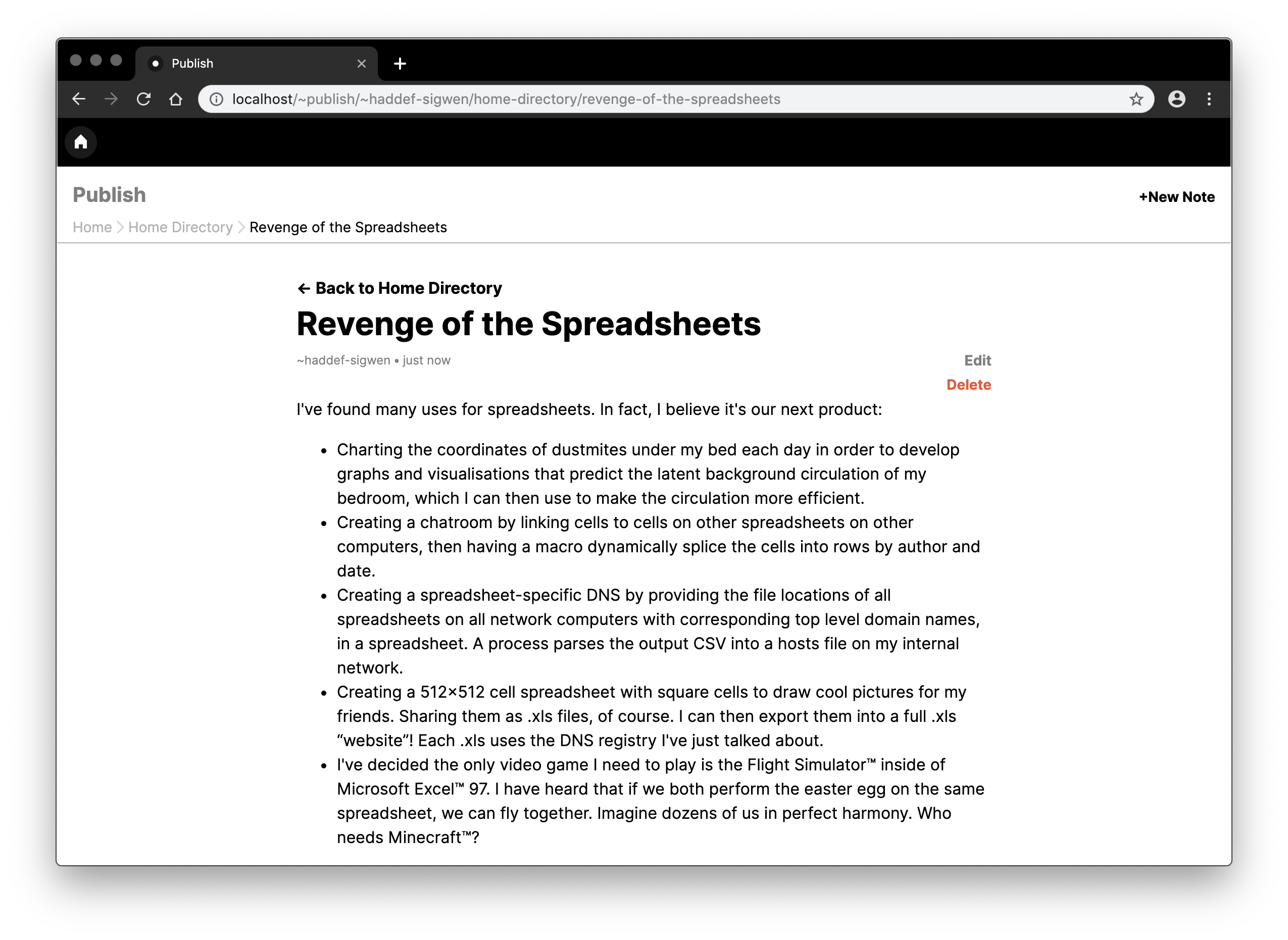

The first set of application includes Chat, a new, streamlined chat client, a basic Weather information tile, an analog clock, and Publish, a place for publishing, subscribing, and commenting on ‘notebooks’ – invite-oriented blogs hosted on your ship.

Our unofficial mantra – “it’s not finished yet” – is performed yet again, but we're close. We can now talk with the broader community about both our inspirations, our visions for its future and our plan to enact that future.

Entering userspace

Urbit has been in “research mode” for most of its history, but the system has now made extensive progress and our kernelspace engineers are the opinionated, confident veterans of the long war you’d expect from an operating system’s early history. The spoils of that war, after rewriting and refactoring all of the system's components several times over, are beginning to really speak for themselves.

Urbit’s kernel is graduating from its rebellious period, however its userspace has remained embryonic for most of its history. The project of building an application model has been restarted and rescoped into aspects that could weather the chaotic growth of the kernel, but it would never quite serve as an interface to the entire operating system. Due to one of our latest vane refactors, it’s becoming possible to start that work in earnest.

Alongside the latest release of Landscape came the rewrite of the %eyre vane, which serves a ship’s files and applications over HTTP. Among the improvements came the decision to move from serving from one ‘/web’ folder by default to an application-specific endpoint.

That is, a Hoon application, upon being started, now tells Eyre it wants to serve these files at this endpoint over HTTP and Eyre facilitates that.

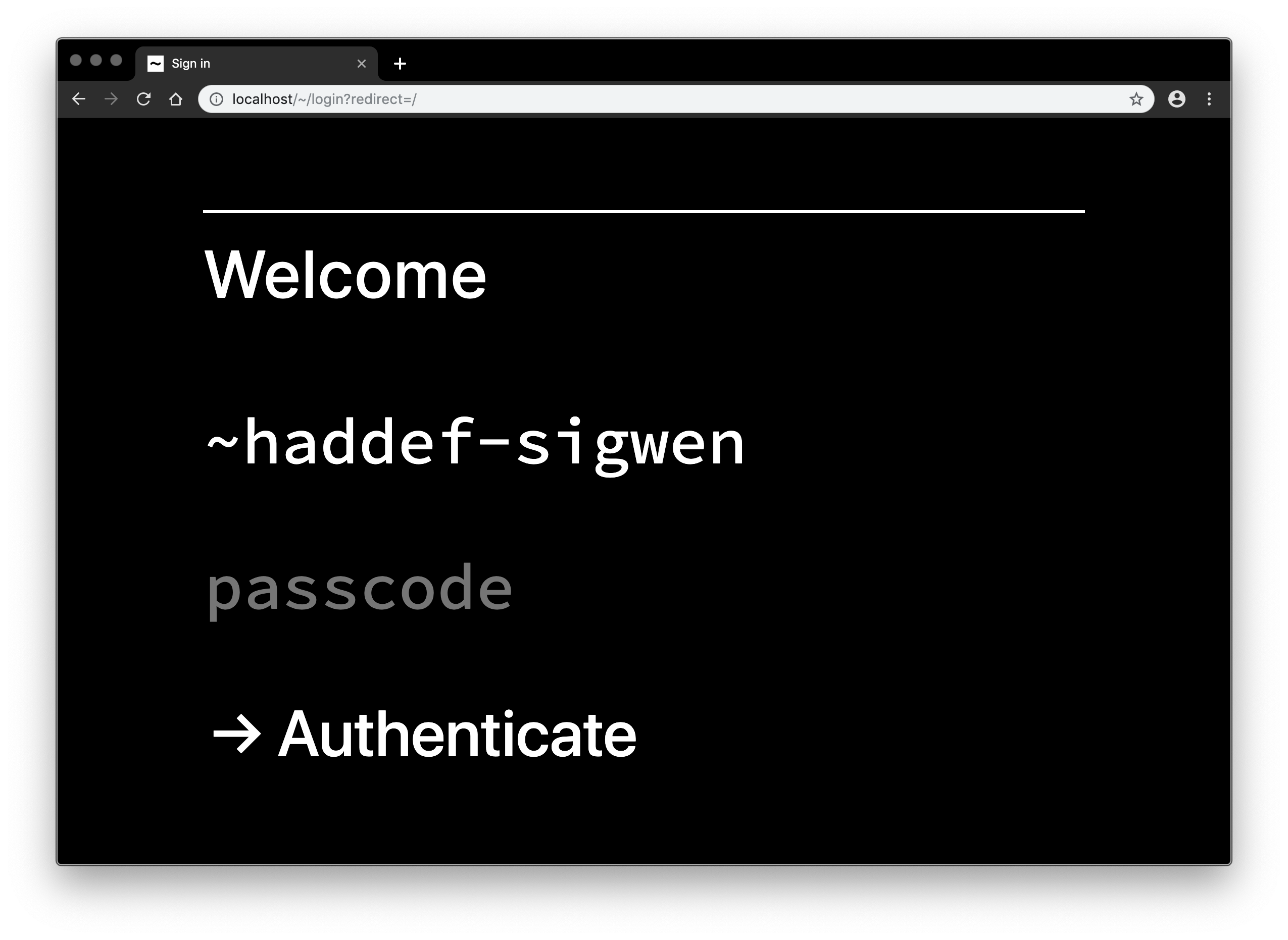

Landscape, with this in mind, serves at the root endpoint (you know, at /). It pre-authenticates the user and provides an API to your ship for applications (and their tiles) to access and poke, peer and scry the ship with.

Whereas, before, a ship had a web server that was good at serving text, but was more obscure for complex (or graphical) applications that made use of the Arvo OS and network, now a ship launches with a web-based interface that makes applications much simpler to experiment with and develop.

If you want, you can just serve files at any endpoint with a boilerplate.

What's more? Arvo access and Hoon logic are now, by default, inside their own application on the ship itself rather than served as inline code on the front-end. This allows for better separation of concerns and more complex and performant applications.

(If you want to play around, there’s an experimental tool you can use to get a full-stack boilerplate running in about 40 seconds.)

All of this is fantastic news; and while Landscape-oriented userspace development is now possible, it’s still not all the way to being an interface to an operating system. For that, we’ve started drawing up specifications and proposals.

Rethinking interfaces

Among the inspirations for our team are the tales of Andy Hertzfeld, working on the Macintosh, and ongoing discussions and decisions that went into Plan 9 from Bell Labs. (Sometimes, for fun, we also watch videos about the Xerox Alto.)

These inspirations share that their creators were dealing with really primordial stuff – the font of human-computer interface had really just sprung and they were seeing things no one had seen before because they had to.

Doing that now, after a lifetime of reflexive familiarity with the dominant solutions – from Apple’s macOS to Google’s Material Design – we have to do the work of unseeing. By engaging with what it was like to see for the first time, we get closer to seeing with fresh eyes. We work to avoid implicitly categorising the new territory as simply, well, comparative to the old one.

So, while it’s not the same to simply read these dialogues, it can get us pretty close.

One reason this iteration of Landscape isn’t the last is because – we must emphasise – this is not the only interface Urbit will have. We aren’t creating a web platform. It should be possible to use just the command-line, and ideally it should be possible to serve windowed interfaces from Arvo itself. It should be possible to SSH into and SMS with your ship, should you want to.

After all, we’re creating a decentralised platform of personal servers with an entirely new stack from the bytecode up. Most of the world’s computers descend from Unix, and Unix was based on timesharing — multiple users in one computer, all pretending it was theirs. Everything since hasn’t left that mindset.

So what do we think that new platform needs from its interface?

Landscape, and all of Urbit’s future interfaces, need a standardised way to view and edit the filesystem. We had circumnavigated this by mounting to Unix, but it’s now time to confront that issue.

Landscape, and all of Urbit’s future interfaces, need a way to easily organise around cohorts of ships, or groups, with shared applications or files and a socially-oriented computing experience in turn — something always in the vision, but not quite implemented yet.

Lastly, Landscape, and all of Urbit’s future interfaces, need a userspace-specific, software design pattern to integrate all of this: access to the file system, permissioning shared sets of files, and tying it together, an underlying representation of both data and interface amongst many computers.

No more siloed input/output in applications on a ‘timeshared computer’ with your redundant data always belonging to someone else.

Into the future

Right now, Landscape applications are still monolithic and geared exclusively toward single-person computing. We hope to change that, and keep communication open with developers so it’s easy for their own development to keep pace with ours.

It should be easy to share whatever data with your friends as you like; to permission files programmatically on a server that is permanently, irrevocably yours.

It should also be easy to read, annotate and discuss a shared book with a specific set of friends; or only allow another set of people to see files in a specific directory if they meet specified requirements.

We will backport these exploratory developments into Landscape as they continue and evolve. This, of course, includes kernel work, as we refactor Gall, the userspace handler vane, and in the process, standardise streamlined practices for writing Hoon in user applications. Take, for example, the async monad, which allows you to avoid dealing with moves or handling each response in separate parts of the application. User applications and Hoon should be both laconic and accessible, and we’re reifying that.

Most importantly, we’ll continue to iterate on how we onboard new developers. Hoon School continues to evolve; its first cohort is thriving and friendly. We have a dedicated cast of teachers and ongoing access to much of the Urbit team through this stream.

If you’d like to join us here, you’ll discover a computer that you can learn and master from the bottom up. Right now, it is a labyrinth for the intrepid; but for the future, and forever, it is mappable. A landscape, after all, doesn’t show a single leaf, but the earth and the horizon ahead.