This is the third in a series of three posts on Urbit address space. See also part 1 and part 2.

It has been some time since we revisited this series of posts, so let’s start with a summary.

Our framework for understanding the value of Urbit address space is that it’s useful, it’s rare, it’s easy to exchange, and the more that people use it, the more useful it becomes. Let’s briefly review each concept in a little more detail.

First, utility. Urbit address space was designed for logging into Urbit OS, but Urbit ID can be used as an identity primitive for any internet service. That means it’s vastly extensible. Perhaps more importantly, because Urbit IDs at the star and galaxy level represent network infrastructure for the Urbit network, users have already begun to build a range of business models upon them, from hosting providers to community hubs. We explored several of these possibilities in detail in the first post in the series, and we also provide a primer on Urbit ID itself.

Second, Urbit address space is finite, and that means it’s scarce. This design, which we explained in more detail in the second post in the series, was intended to promote good behavior and to limit spam. So far, that has worked. Scarcity is also impacted by availability of supply, which we’ll explore in this post.

Third, network effects, also described in the second post in this series, have the potential to build upon themselves quite rapidly within the Urbit ecosystem. Urbit is essentially a network of other networks, each owned and controlled by their individual users. For this reason, Urbit’s network effect is best described by Reed’s law, which argues that the value of a network increases with the number of groups that can be built on the network. In Urbit’s case, this number is essentially bounded only by the amount of data that can be stored in Urbit itself, which today is 2GB. That size is already enough to support vastly more groups than anyone has tried to launch, and we plan to grow beyond that limit in the coming year.

Also in Part 2, we explored trading of Urbit address space. We look at the current price of stars and planets as denominated in both BTC, and USD, and we see that the price of Urbit address space has remained fairly constant since its launch on-chain, while volume has been steadily increasing. The market is continually developing, with more ways to buy and sell Urbit address space cropping up.

So, to recap: our view is that the value of Urbit address space is a function of its utility, scarcity, network effects, and ease of trade.

In this post, we don’t expand that framework, but rather explore two elements that are important to actually using the framework. We’ll explain lockups, since they impact scarcity, and we’ll discuss usage metrics — including why we don’t (and in most cases can’t) track them.

Lockups and spawning limits

One way to think about galaxies, stars, and planets is that they’re different-sized buckets of Urbit IDs. A star contains 2^16^ (~65K) planets, a galaxy contains 2^8^ (256) stars and, in turn, 2^24^ planets (16,777,216). Beyond this nesting pattern, there are three further considerations to note: booted versus unbooted addresses, locked versus unlocked addresses, and planet spawning limits.

Booted and Unbooted Addresses –

A booted address is one that has actually been used to boot Urbit OS. By convention, booted addresses are expected to have some existing reputation outside of their name alone, since they’ve been used on the network. Reputation, good and bad, comes in many forms. Did the address operate any useful infrastructure? Did it get placed on any blacklists for spam or abuse? Did it simply send and receive messages? The ability to programatically track reputation is still in its infancy, but we expect the tooling to develop as Urbit grows.

Unbooted addresses, on the other hand, have no reputation. Both booted and unbooted addresses can be transferred between owners, but booted addresses will likely vary widely in price depending on the reputation each of them has acquired, and how they’ve been used.

For the purposes of this discussion, we’re primarily referring to unbooted addresses, as they have no reputation, and so are more similar to one another. We anticipate that booted addresses will trade infrequently — and likely via broker or auction, since users will prefer to control the reputation of the ID they’ve developed, rather than transfer that reputation to another.

Locked vs. Unlocked Addresses –

At present, the majority of Urbit address space is locked by smart contracts. When Urbit address space was first registered on the Ethereum blockchain, this unlocking mechanism was put in place to prevent the network from being flooded with users. A young Urbit network in which all of the address space had been unlocked would be exposed to attacks by bots and spammers. Scarcity, on the other hand, encourages good behavior as it increases the cost to spam.

A locked star is held in a contract and can neither be booted nor issue planets. The lockup contracts can be examined on GitHub.

In practice, the only Urbit IDs that are ‘locked’ are stars. A galaxy that is said to be locked is simply a galaxy whose stars are currently held by a lockup contract. A locked galaxy can be transferred (i.e. sold or simply moved to a new key) and booted (importantly, any galaxy—booted or not—can vote), but it can’t issue stars until the lockup contract expires.

These lockups all began to release at varying linear rates in January 2019 (specifically on Tue Jan 08 23:34:41 2019 UTC).

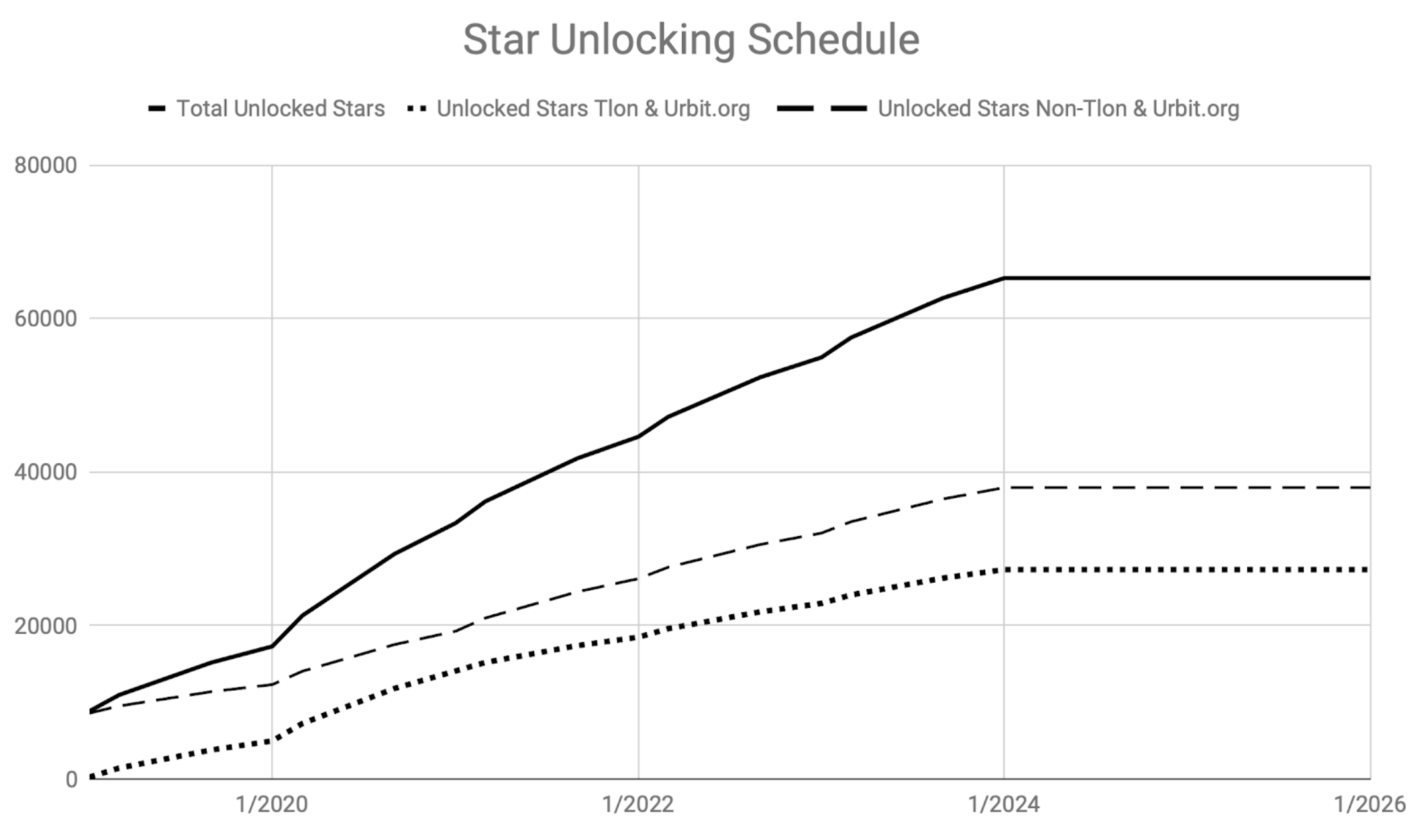

The various linear unlocking schedules are grouped as follows:

- The urbit.org addresses, and early prize winners unlock linearly from 2019-2021.

- Tlon, its founders, employees, and most purchasers from Tlon were frozen for a year, and now unlock linearly from 2020-2024.

- 2018 private buyers were frozen for a year, and then began to unlock linearly over the course of one or three years, depending on the terms of their respective contracts.

- Earlier private buyer addresses—including those in our first two crowdsales—were unlocked right away.

As of January 2020, 17,283 stars were unlocked and tradeable. By January 2021, 33,355 will be available. On January 9, 2024, all 65,536 stars will be unlocked and available for trading.

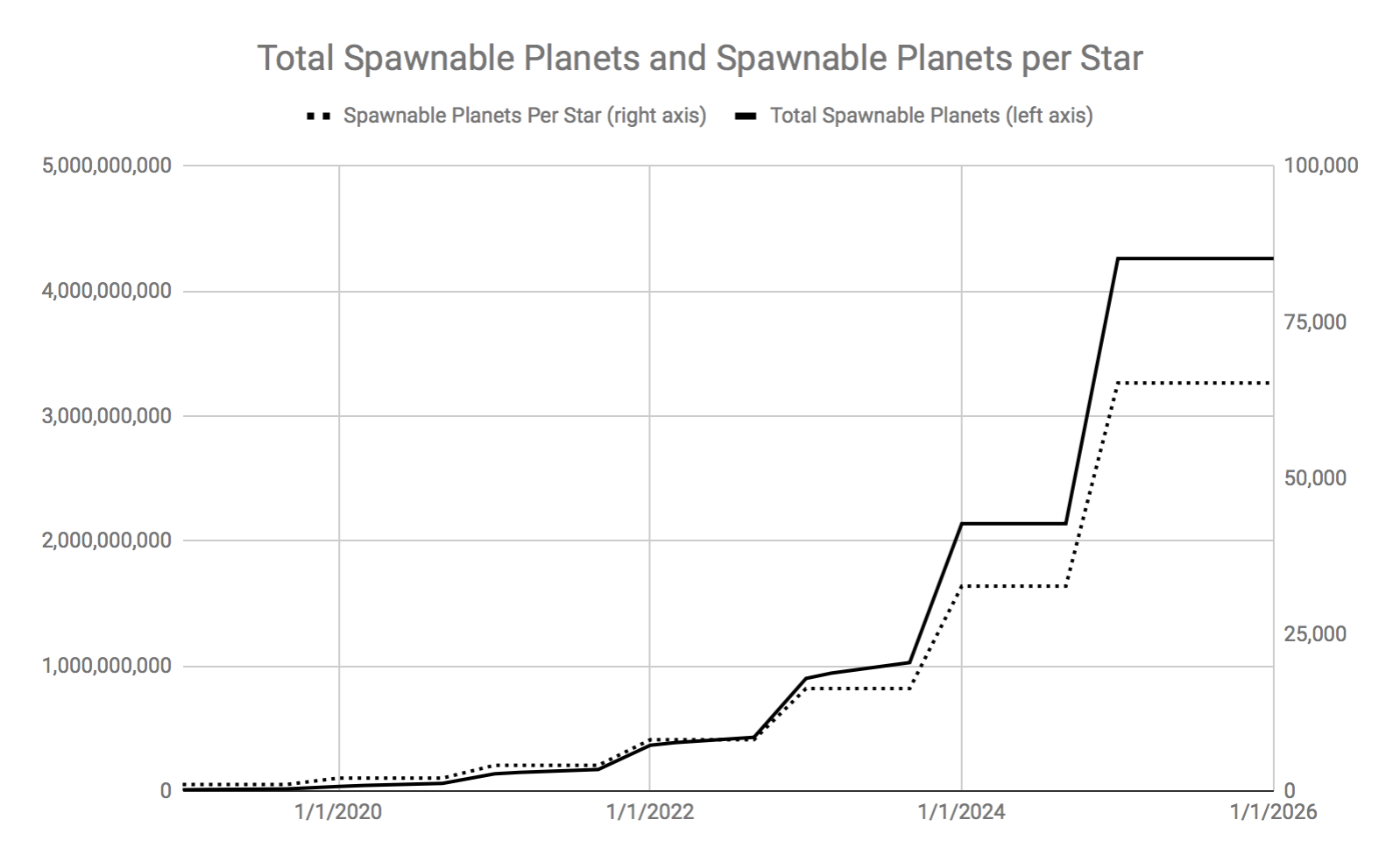

Being unlocked does not necessarily mean that a star can spawn all of its planets. For that calculation, we must turn to spawning limits.

Spawning Limits –

Unlocked stars are further gated by the number of planets they’re able to spawn. Every unlocked star was immediately able to spawn 1024 planets from the moment Urbit went live on the blockchain in January 2019—we wanted everyone to be able to invite some friends to their communities right away. From that date forward, the spawnable amount doubles every year (365 days), maxing out at 65,535 spawnable planets after 6 years.

When we layer the spawning limits over the various lockup contracts, we find that all Urbit address space is both unlocked and spawnable by January 9, 2025.

Address space distribution

Address space has continued to change hands since we put Urbit on-chain in January 2019. At that time, we had a fairly granular understanding of who owned what. Today we only have precise numbers for the Tlon and urbit.org owned address space. Galaxies change hands quite infrequently, so we know more about that ownership than stars and planets. We know next to nothing about the distribution of planets.

We consider the opacity of our understanding about transactions on the network to be a privacy feature rather than a bug. To be specific about the information we can collect here: first, we don’t know anything about users beyond their ETH address, and second, we can’t tell the difference between a transfer of an address, and the re-keying of an address. This means we’re never entirely sure if a transfer has in fact occurred; we only know that the address has changed.

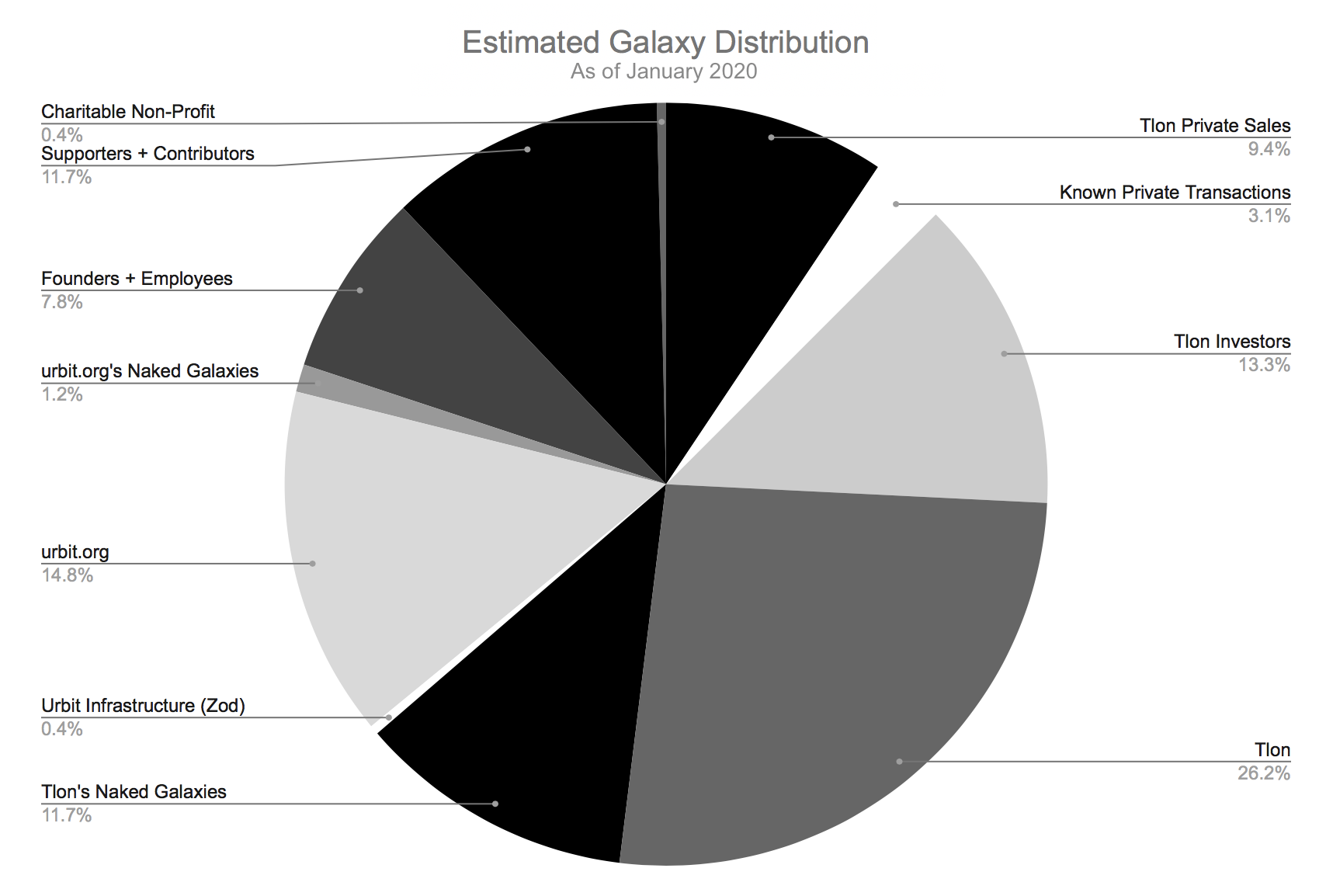

The chart below is an estimate (as of January 2020) based on our general understanding of how galaxies are distributed. Much of this is anecdotal, and it’s largely based on the very few transactions we’ve observed within the galaxy table since Urbit went on chain in 2019. This chart should therefore be understood as incomplete, and an estimate only.

Address space distribution is best understood in terms of galaxies and stars independently, as they’re distinct assets. The chart above only illustrates galaxy distribution, but describes Tlon’s “naked” galaxy holdings, which are galaxies empty of their stars. These galaxies are empty because the stars they once contained have been distributed, primarily to Tlon contractors, employees, and to certain private buyers.

We believe that wide distribution is important to the health of the network and the growth of Urbit as a whole. Our own distribution efforts are focused on disbursing Urbit address space ownership as broadly as possible to those interested in using and developing the network.

We intend to further distribute Tlon’s address space over the coming years through private sales, employee compensation, grants, bounties, and gifts. It’s worth noting that the grants and bounties program specifically is set to increase in coming years. We’re very much interested in putting address space in the hands of people interested in helping develop the network; we see grants as the perfect mechanism for doing so.

Usage data and composition

Usage data is an obvious missing piece of the puzzle in this discussion. We understand this, and yet we don’t actively capture usage data, for two important reasons: it’s premature, and Urbit is privacy-focused by design.

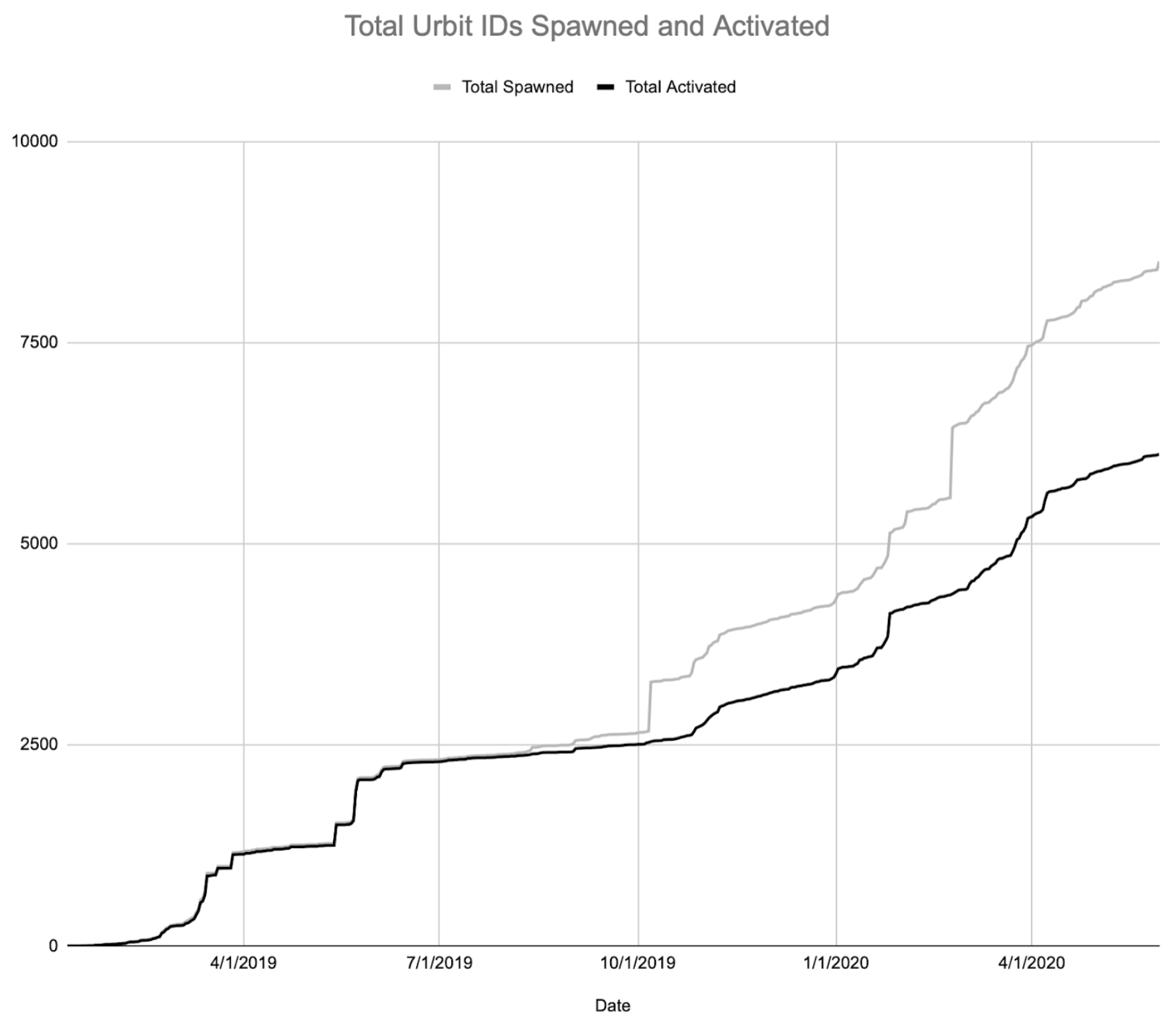

First, it’s too early. Urbit’s current users are a fanbase of pioneers who are willing to put up with the challenges of a young network. This fanbase grows on its own, but Tlon doesn’t actively encourage that growth yet. For the vast majority of potential users, the barriers to entry are still high enough that an invitation would risk losing them permanently. You can think of Urbit today as being a developer alpha.

We’re laying the groundwork so that we can, in earnest, invite our friends and communities to a network they will love. That means we’re designing smooth onboarding, an elegant user interface, and increasing the stability of both the system and network. Tlon’s forthcoming hosting services will vastly reduce barriers to entry, and will be our first major push into the public sphere.

Second, and perhaps more importantly, capturing data about traction on the network is difficult by design. Due to Urbit's privacy-forward architecture, there’s quite a lot we will never know. Once an Urbit ID is up and running, we don’t know how often it operates, where it’s hosted, or what it’s doing. This makes capturing usage metrics challenging, but we think this is the right problem to have.

The Network Explorer –

In the next several months we plan to roll out the first iteration of a network explorer that will allow users to visualize the structure and composition of the network as well as some basic activity data. Our first version of the network explorer will include representations of how the various layers of address space fit together, the finiteness of address space, historical uptime for nodes, and the various unlocking schedules. The network explorer will also allow users to zoom in on various nodes to learn more about them and what they offer. Urbit’s privacy-forward design makes collection of data appropriately impossible in many cases. That said, the network explorer should begin to collect all the elements of the value framework we’ve laid out here in one dynamic visualization.

Closing –

We have long said that Urbit address space had value because it was both useful and scarce. Taking a deeper look, we found that some limited liquidity, and network effect also play an important role in the value framework.

All of the factors that make up our framework are, in turn, impacted by availability of supply and by user growth. In the Urbit ecosystem, supply is effectively gated—as described above—in order to prevent flooding of the network.

User growth, on the other hand, is something we simply have not yet pursued in earnest. Instead, our development efforts have been focused on enhancing usability and stability of the platform. Our focus on user growth will begin as we roll out hosting. Once that happens, usage metrics will become both more interesting and more relevant.

This concludes the final installment of our series on the value of Urbit address space. Though the explanation was long, the framework is quite simple: value in Urbit is derived from its use, scarcity, some liquidity, and network effect. Let us know if you’d like us to dig deeper into any of these elements—we’re always happy to opine about Urbit.