Recently, the first upgrade to the Azimuth smart contracts which make up Urbit ID was put up to an upgrade proposal vote by the Galactic Senate. This vote is still open and will last for 30 days (June 20th) or until an absolute majority is reached. We’d like to take this opportunity to discuss two things. First, what the proposed changes are, and second, a review of how Urbit governance works and where we’re at in the decentralization process.

Before we dive into what the proposed changes are, let’s review what the Senate is actually capable of changing. Urbit ID is really two sets of smart contracts: Azimuth and Ecliptic. Azimuth is the data of the public key infrastructure - roughly, this is the list of ships and which Ethereum addresses own them, along with other data such as networking keys and sponsorship status. The Senate has no ability to touch this data directly. This is in direct contrast to all existing centralized services, where your account is always at risk of being taken away from you. What the Senate can change is Ecliptic, which is the “business logic” that decides how you can interact with the data in Azimuth. These are mechanisms such as what powers various proxies have, how stars/planets are released over time, and how sponsorship works. Put another way, the data and database format must remain the same, but the rules by which we interact with it may change according to the governance rules we detail below.

Changelist

The Galactic Senate is voting on the following changes to Ecliptic:

- Fixed ERC721 compatibility

- Self-modifying proxies

- Upgraded Claims contract

Fixed ERC721 compatibility

In Ecliptic, the contract includes various functions and events that make it conform to the ERC721 (non-fungible token) standard. However, two events have ever so slightly non-confirming descriptions. This causes Ethereum explorers like Etherscan to incorrectly recognize Azimuth as ERC20 (fungible token), rather than ERC721.

The proposed change simply modifies the event descriptions to accurately match the ERC721 definition. This does not affect any functionality within the contract itself.

Self-modifying proxies

Owners of Azimuth assets are allowed to configure "proxy addresses" for those assets: Ethereum addresses allowed to act "as" the owner, but only for a subset of operations. For example, setting the management proxy will let you change your networking keys and sponsor using that address, just like your ownership address can. This is useful for keeping the ownership keys in very cold storage while still letting you perform lower-value operations.

Currently, only the ownership address is allowed to change proxy addresses. Fairly early on after Azimuth's deployment, we realized it might be nice for proxies to be able to change themselves.

This means that, in addition to being able to configure networking keys and sponsorship, your management proxy would be able to assign a new management proxy. This would allow you, or a trusted third party holding your management proxy, to rotate your proxy keys without needing to take your ownership keys out of cold storage.

Upgraded Claims contract

The Claims contract lets asset managers associate various "claims" with their identity. For example, an Ethereum address to send donations to, or proving ownership of a Twitter account.

For ease of use by off-chain tools and services, the contract emits events (notifications) whenever any claims are updated. However, the current version of the contract has a bug where it does not emit events when all claims are removed at once (clearClaims()). This "gap" in the event stream makes it much more difficult to write off-chain tools around this contract. Considering Claims has seen practically no use since it was first deployed, it should not be a problem to simply start over fresh with a new contract that contains the fix for the described bug.

The reason we must do an Ecliptic upgrade to switch to a new Claims contract, is that it is tied in with the logic for transferring an asset. If an asset is flagged for "reset" (common when transferring to/from someone other than yourself), its configured proxies, networking keys and claims are cleared during transfer. As such, Ecliptic will need to know about the address of the new Claims contract.

Urbit Governance

The ultimate goal of Urbit is to become a digital republic manifested as a peer to peer network owned and controlled by its users. The goal of Tlon, then, is to become one of many companies who build products for Urbit rather than being the primary driving force behind its development. We’d like to take this opportunity to spell out our perspective on where we’re at in that process. Here are some previous posts that are relevant, but please note that some of them are several years old and as such may not accurately reflect our current position, but still serve as useful historical markers. We hope to revisit and refresh these documents soon.

- 2016.5.16 - Interim Constitution

- 2016.5.16 - The Urbit Address Space

- 2016.6.24 - The DAO as a Lesson in Decentralized Governance

- 2019.1.11 - Governance of urbit.org

Galactic Senate

The Galactic Senate is composed of all galaxy holders, which at present consists of more than 100 individuals and a few organizations, including Tlon and the Urbit Foundation. Using the Azimuth voting contract, the Senate can present and vote on two kinds of proposals: document proposals and upgrade proposals. Thus far, all matters which the Senate has voted on have been document proposals. The most recent vote declared the Urbit network as (i) being secure (as confirmed by a third party audit) and (ii) having reached continuity (as in, no further network breaches are expected). Previous votes were to declare that Azimuth is live and that Arvo is stable.

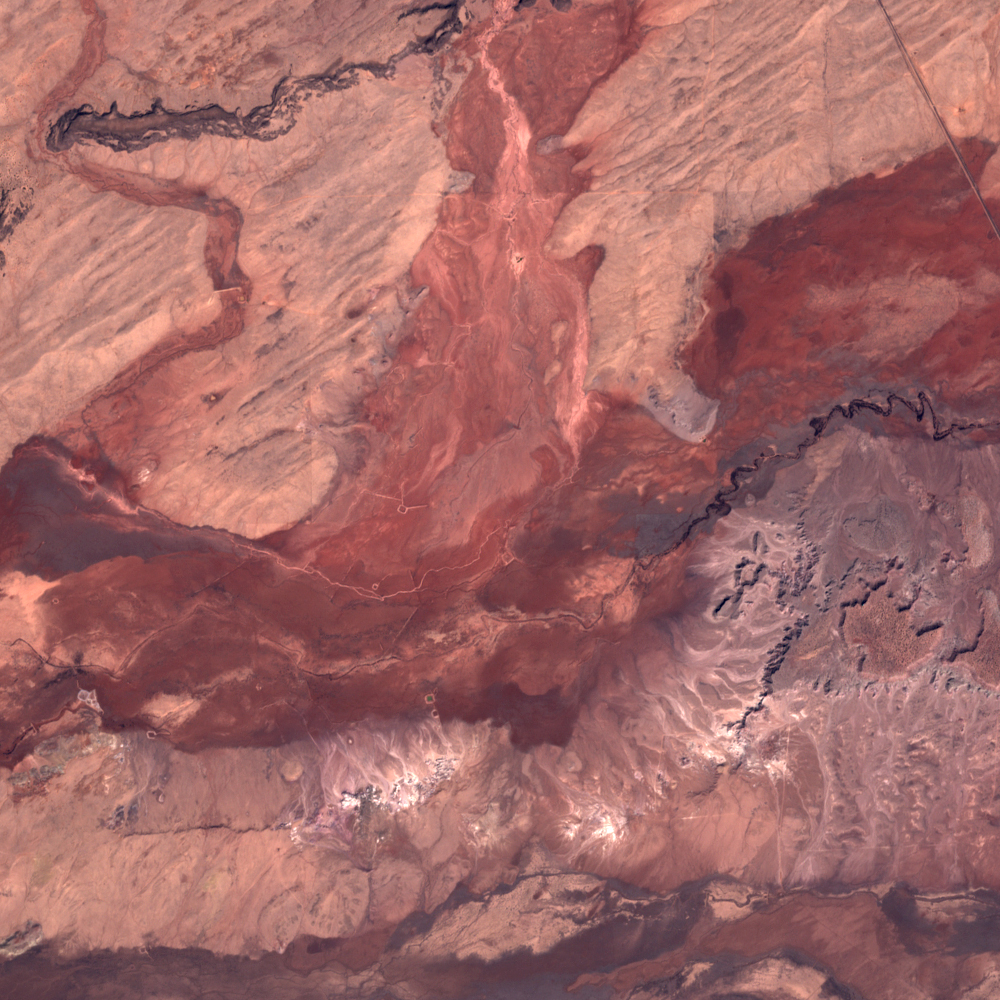

Address space distribution

Perhaps the most informative measure of how decentralized Urbit is in terms of how many independent parties hold address space. By the very nature of Urbit, it is impossible to know this with great accuracy (a common feature of decentralized projects). However, the movement of galaxies is closely watched and thus we have a fairly good idea of how distributed they are.

In the beginning, Urbit’s creator Curtis Yarvin was in possession of the entire address space - all 256 galaxies, and everything underneath it. A network of one is no network at all, and so over the last decade Urbit’s development has been primarily driven by selling or giving away these galaxies. On June 1, 2016, the allocation was:

95, to the Tlon Corporation. 50, to urbit.org, the future community foundation. 40, to Tlon employees and their family members (24 to Curtis, who started in 2002; 16 to everyone else, who started in 2014). 34, to outside investors in Tlon. 37, to 33 other individuals, who donated to the project, contributed code or services, won a contest, or were just in the right place at the right time.

Since then, Tlon has sold a number of its galaxies to fund development and others have changed hands to the point that Tlon and urbit.org no longer possess a majority share of galaxies. In January 2019, Curtis gave all of his galaxies to Tlon when he left the project. In August 2020 we shared an update on the known distribution of address space, where Curtis’ galaxies are marked as Tlon’s “naked galaxies”. Shortly thereafter, Tlon disbursed its naked galaxies among the employees that wanted one who did not already possess one, thus removing Tlon and urbit.org’s controlling share of the Senate. Galaxies held by current and former Tlon employees are entirely independent of Tlon Corporation—they may do with them, and vote with them, as they please. ~ravmel-ropdyl plans to give more color to this decision in the near future.

Distribution of stars is much more difficult to know. There is an active market for stars on OpenSea, so we know that they are changing hands frequently, but checking the number of distinct Ethereum addresses that hold stars does not tell you very much information since a single person can control multiple adresses.

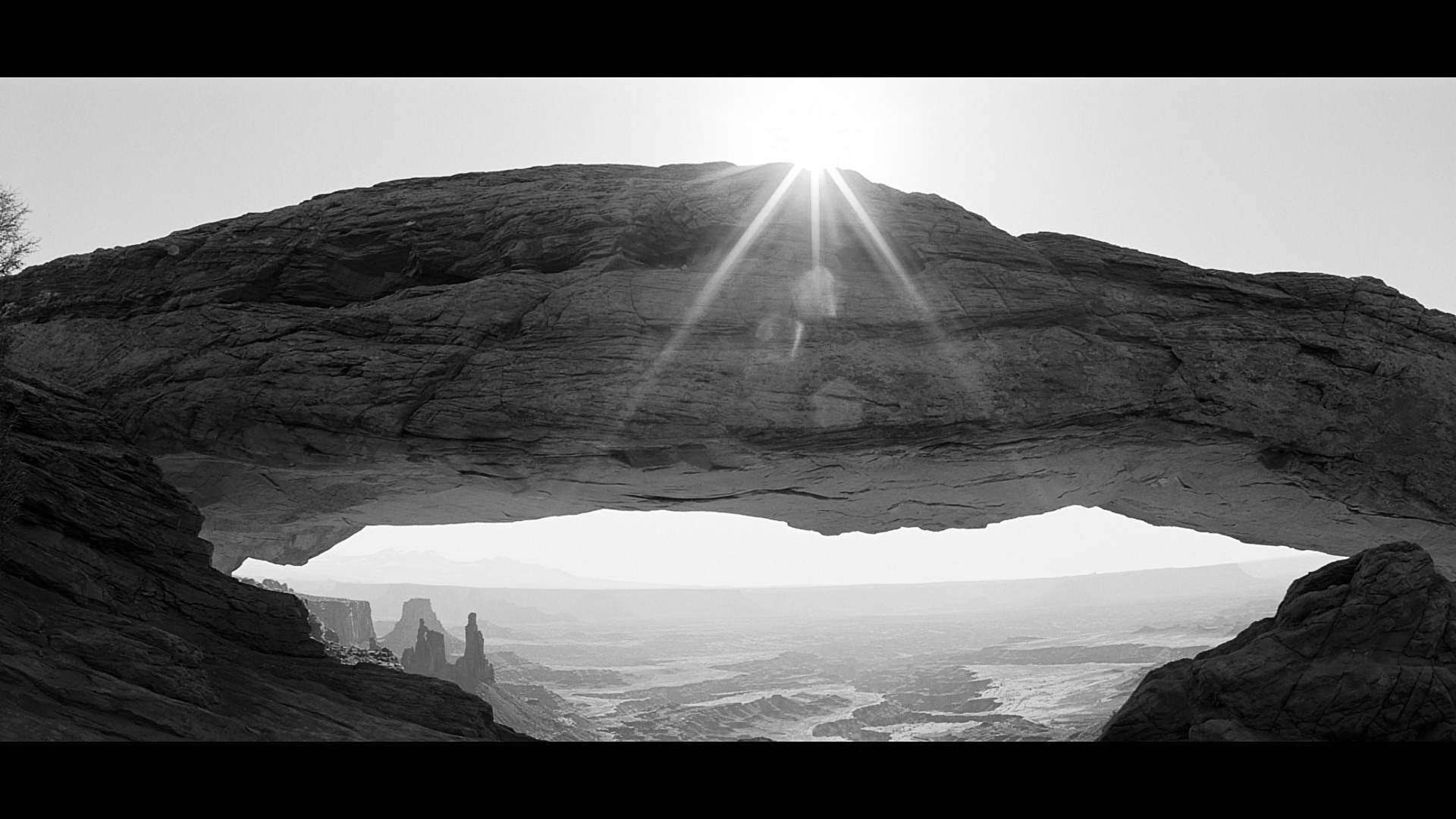

Software and smart contracts

As was written in The DAO as a Lesson in Decentralized Governance, we are keenly aware of the threat of decentralization theater. Urbit has undergone steady progress towards decentralization, and with the developments we outline below, it’s never been more clear that the project is beginning to leave the cradle of Tlon. It’s also important to note that the decentralization of a project is always a movement away from an initial centralized state—you cannot go from A to Z without first traversing every letter in between. While Urbit was centralized at the beginning, the journey towards a network owned and controlled by the users is now well underway.

In the past, nearly all Urbit software was written by Tlon. While Tlon is still the only corporation actively updating Urbit’s MIT-licensed open source software, namely Vere (the runtime), Arvo (the kernel), Landscape (the client), and Bridge (the ID manager), unaffiliated individuals have been making enormous contributions to Urbit over the past couple of years via the grants program. Recent examples include the Bitcoin node and wallet integration, WebRTC integration, Port, an Urbit installer and ship manager, and |fuse, an important primitive for 3rd party software distribution.

The only real power Tlon holds over Urbit is the ability to push OTA updates via ~zod, and suggest that people download our binaries. To the best of our knowledge, all extant galaxies retrieve their OTA updates from ~zod, who forward it to their stars, who forward it to their planets. This software distribution route is merely a convenient default setting. Ships initially retrieve OTA updates from their sponsor, but they have full authority to retrieve updates from whoever they want with the |ota command, or even to only install software updates by hand if they so choose.

In the future, one can easily imagine many organizations shipping their own distributions of Urbit from their own urbit nodes, somewhat analogously to the large number of Linux distributions which exist today. There is nothing we can do to stop a group from forking Urbit, declaring ~sampel-palnet the new ~zod (both for updates and for sponsorship purposes), and retrieving all OTA updates via that route and building their own binaries. This is all by design, and we wouldn’t want it any other way.

The use of the Azimuth smart contracts is also somewhat optional. By changing a few lines of code to point their ships at another set of PKI smart contracts, they could rid themselves of hierarchical peer discovery entirely and make use of some other routing strategy such as Kademlia based DHT routing. This would likely give rise to an entirely separate network. The fact that the network is fully capable of such a schism helps keep the Senate honest and accountable to the users. If they ever were to vote on a contract modification that greatly angered or upset a portion of the user base, they would be inviting such a schism and be entirely deserving of it. In that sense, the power to control the network is already held by the users, they just have not yet had a reason to make use of it.

Legitimacy

The only way by which Tlon and the Senate hold any power is via legitimacy. Vitalik Buterin recently wrote a very informative article on the role of legitimacy in decentralized governance, and I do not know of a better source to understand how Tlon and the Senate are kept in check by the users. Besides the DAO split resulting in Ethereum and Ethereum Classic mentioned in the article, perhaps the most prominent example of the power users have over a decentralized network is the saga of Steem and Justin Sun. The short version of the story is that Justin Sun bought a controlling share of the Steem blockchain and attempted to exert control over it, and the users banded together to fork the blockchain into one called Hive, which was identical to Steem except with Sun’s token balance set to zero. An analogous outcome for Urbit would be that the Senate makes sweeping changes to the PKI and invites a schism like that outlined above.

For these reasons, there are strong disincentives for any one organization or individual to acquire too many galaxies. If galaxy ownership becomes more centralized, individuals will be less incentivized to build on the network which will reduce the value of address space. Furthermore, such centralization might provoke a fork if such centralized powers are perceived as malicious by the users. This is in contrast to real-life republics, where there is little risk for one party to accumulate as much power as they can manage since the cost to the citizens to overthrow that power is enormous. Thus, only especially egregious displays of power ever result in rebellion. Within the Urbit republic, users need only to change the code they run to leave the Senate powerless, and so the threat of rebellion is much more real. We estimate that within a digital republic like Urbit, the centrifugal forces outweigh the centripetal forces, and that the outcome of this is more stable than the reverse.

Why have governance at all?

An important question the reader may still have lingering is: why does Urbit need governance at all? The short answer is: (i) there will always be necessary protocol upgrades that cannot be foreseen, and (ii) a total lack of governance inevitably gives rise to a shadow government with undefined powers that is almost impossible to hold accountable.

With (ii), we see this to be the case on many early blockchain projects where power is shared by the developers and the miners, but what each is capable of doing has never been codified, and thus users of the blockchain can never have a great deal of certainty of what changes might occur in the future. This doesn’t guarantee a bad outcome, but it does create more wariness among developers when they cannot know whether they really have a say in the project's direction. Recognizing this issue, many newer blockchain and blockchain-adjacent projects have built-in governance mechanisms that lay out exactly what an individual can expect should they join and contribute to that network.

As for (i), with Urbit being a wholly new kind of network, it would take incredible luck to get the PKI exactly right on the very first try without ever needing another modification. Thus, some mechanism was needed to guarantee that the PKI’s logic could be altered. Leaving control of Azimuth in the hands of Tlon would have just granted Tlon dictatorial power, which Tlon nor Urbit users desired. There’s certainly room to argue that the Galactic Senate is not a perfect system: our interim constitution did outline potential roles for stars and planets to play in governance in the future, so there is ample opportunity for the system to evolve in response to the will of the users. As always, it is important to keep in mind the unfinished nature of the Urbit of today and the still moldable clay of the Urbit of tomorrow—nothing yet is set in stone.